Ein Programmschwerpunkt von „Narrating Africa“ gilt Namibia. Wissenschaftler:innen und Schriftsteller:innen aus Namibia stellen Texte und Dinge aus Namibia vor.

Meameno Aileen Shiweda / "Owela"

A. Meameno Aileen Shiweda about herself:

I am a lecturer of English Language Education in the Department of Education in Languages, Humanities and Commerce at the University of Namibia (Hifikepunye Pohamba Campus). I hold an MPhil in Intercultural Communications from Stellenbosch University. I am currently completing my PhD degree at the same institution. My research interests are language biographies, specifically their role in improving language use and the teaching proficiencies of languages students, as well as code-switching and multilingualism. I also have experience in teaching children’s literature as well as young adult literature.

B. I chose this object because …

The object, or to be more precise, game or activity I chose is ‘Owela’ – an enjoyable mathematical pastime that is similar to chess. It is played on the ground, normally under the shade of a good tree where the players dig small holes and use pellets, stones, or dried marula fruits. There are normally four rows of twelve holes. Two opponents sit on opposite sides facing each other and set up the game: each player is given twenty-four pellets and they use the pellets to claim twelve holes, which are arranged across two rows (six holes per row). The players fill ‘their’ twelve holes with the pellets (two per hole), but in each row the two holes on the left and right sides must be left empty. The first player then begins by taking the two pellets from the first hole and then placing one in each of the following holes in sequence. The other player repeats the same thing on their side until all pellets are rearranged in such a way that their side contains no hole with two pellets (instead the holes have only one or more than two pellets in them). The first player who manages this wins the game. I chose this activity because it is interesting that participants are usually unaware of their ability to think critically on their feet in order to solve the calculations involved in this enjoyable activity.

D. What do I find fascinating about this game?

What I find fascinating about owela is that those who play it are often unaware of their mathematical abilities, which they often do not link to other situations in life that require such skills.

E. What information do I think is important to understand this object?

Owela is enjoyed in the summer when people are done with their work in the fields because there is usually nothing else to do to pass the time. A basic understanding of arithmetic is necessary for one to succeed in playing owela. Two objects in a hole are called ‘eedidi’ whereas a full hole is referred to as ‘omaxwixwi’. One item in a hole is called ‘kamwi’.

F. Which questions regarding this object have I not yet found an answer to?

The main question I have is why this activity has not led to those who play it developing further mathematical skills that they can utilise in other educational contexts. I find it baffling that this knowledge is not transferred to other areas. Often, you encounter people who are geniuses at playing this game, but in other situations they are unable to count correctly.

Foto: Basler Afrika Bibliographien

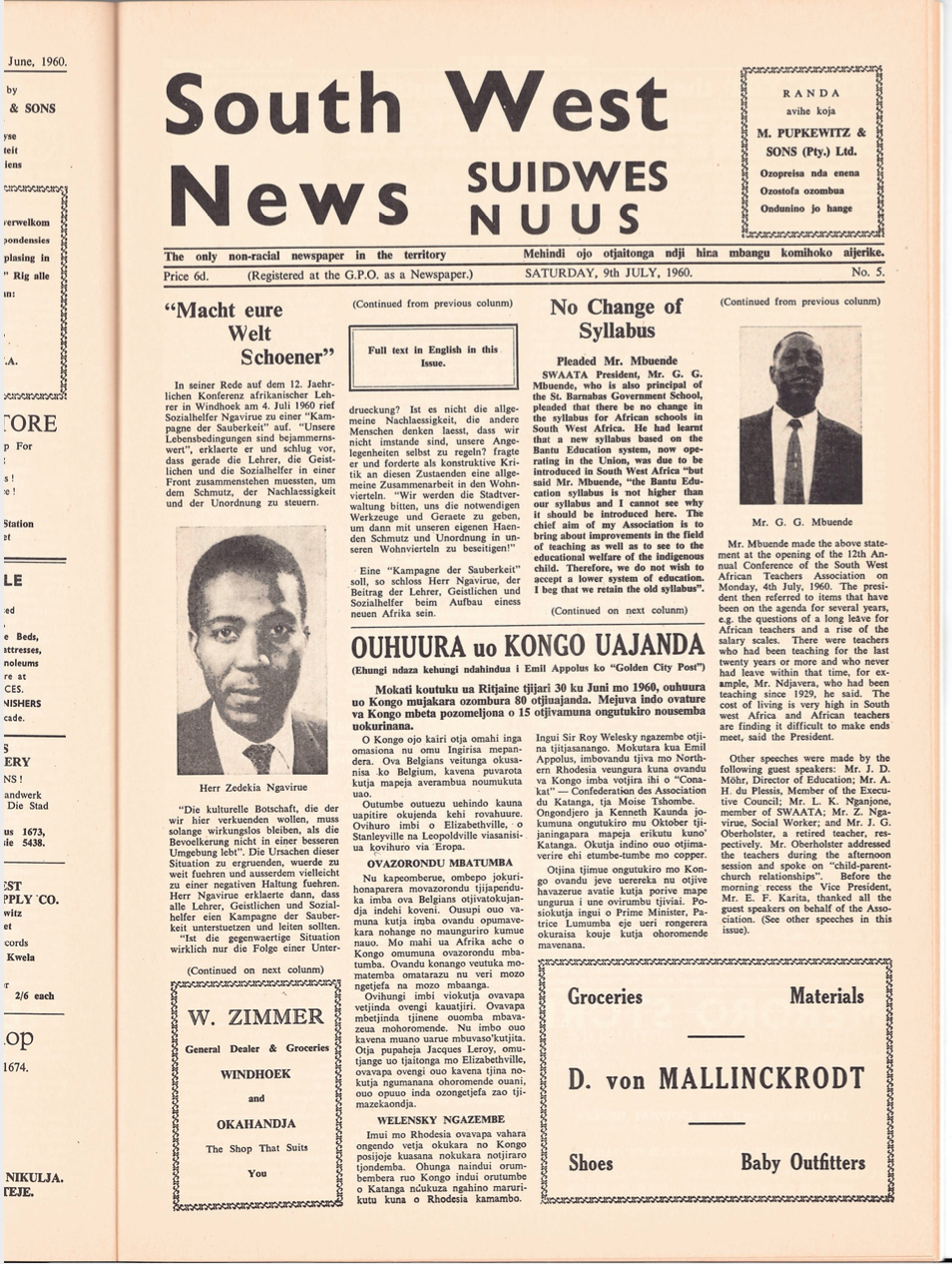

Dag Henrichsen / "South West News"

„Ich habe die ‚South West News – the only non-racial newspaper in the territory‘ aus Windhoek vom 9. Juli 1960 ausgesucht, weil das die erste afrikanische Zeitung in Namibia ist – und die einzige ’non-racial newspaper‘. Sie wurde 1960 im afrikanischen Township von Windhoek von jungen afrikanischen Aktivist:innen herausgegeben.

Die hier ausgewählte erste Seite mit Artikeln in Deutsch, Englisch und Otjiherero gibt u.a. in deutscher Sprache eine Rede wieder, die Zedekia Ngavirue auf dem Kongress der afrikanischen Lehrer:innen in Windhoek über die Themen ‚Unterdrückung‘ und ‚Selbsthilfe‘ gehalten hat.

Die Zeitung ist für eine multilinguale Leserschaft im von Apartheid bestimmten Namibia gedacht. Afrika wird – auch auf Deutsch – für ‚weiße‘ und ‚schwarze‘ Afrikaner:innen in Afrika erzählt und gestaltet. Im multilingualen und multikulturellen kolonialen Namibia nahm die deutsche Sprache und das Narrativ ‚Afrika‘ einen vielschichtigen Platz ein.

Zedekia Ngavirue ist heute (2019) der Sonderbeauftragte der namibischen Regierung zu den namibisch-deutschen Verhandlungen. 1960 war er der erste afrikanische Sozialarbeiter in Namibia.“

Napandulwe Shiweda / "Ekola" (singular), "Omakola" (plural)

A. Napandulwe Shiweda about herself

I am the Head of Social Sciences Division in the Multidisciplinary Research Centre (MRC) at the University of Namibia. I hold a PhD in History from the University of the Western Cape. My research addresses the new category of colonial intermediaries and contestations over political and social legitimacy through memorials in Namibia and Angola. I am also a senior lecturer of Visual Culture in the Department of Visual and Performing Arts at the University of Namibia, and have overseen projects at the Museums Association of Namibia (MAN) and the Archives of Anti-Colonial Resistance and the Liberation Struggle (AACRLS) at the National Archives of Namibia.

B. I chose this object because …

„Ekola“ (singular) „Omakola“ (plural)

This is a musical instrument in the form of a notched bow mounted on a resonator consisting of two coupled calabashes. It is played with two hands, one holding a simple stick, the other a bundle of sticks. The dimensions vary quite a bit. The semi-circular curvature of the arc is held by a double strap which passes through the two calabashes. I chose this object because it is an interesting musical instrument that can no longer be found in northern Namibia.

C. What narratives of Namibia do we encounter in it? Which sentence can be used to illustrate this?

The instrument was used during rituals to deal with mental illness, but also when traditional healers were graduating to a higher level of recognition. The missionaries in northern Namibia suppressed the instrument and condemned practices associated with it as they were seen as pagan.

D. What do I find fascinating about this object?

It is fascinating that the calabashes („omakola“) themselves are firmly tied to each other using relatively simple material: bark, thatch, and cow dung. The pass of the largest calabash enters the bottom of the smaller one. Most often the two calabashes have a round hole which is located under the arch and this position is maintained by ligatures securing the arch to the resonators. To play the instrument, one uses both hands, the instrument placed in front of you on the ground.

E. What information do I think is important to understand this object?

I think it is important to gather information and create awareness of the history of this object in order to understand it, especially since it was essentially associated with homosexuality and was played by a medicine man who apparently encouraged this practice. „Ekola“ was also played secretly and only in the presence of men. Thus, it is important to know whether these were some of the reasons that led to its suppression by missionaries. It is also important to know the ways in which this impacted people in northern Namibia in the past and in the present.

F. Which questions regarding this object have I not yet found an answer to?

I still have not found an answer to the question regarding this object’s link to homosexuality – more research is needed to think about how this object could be used to address gender inequality or homophobia, and to start conversations in northern Namibia on the topic.

Lade Audio…

Dag Henrichsen / Interview mit Cecilie Kapepera Kahimunu (1990)

„Cecilie Kapepera Kahimunu (geboren 1914/15) berichtet von ihrer ehemaligen Tätigkeit als Hausangestellte und Köchin auf einer deutschen Farm in Namibia.

Das auf Deutsch geführte Gespräch enthält zahlreiche pointierte Wahrnehmungen über die deutsch-kolonialen Verhältnisse, wie sie eine afrikanische Dienstbotengesellschaft erlebte und nun, in der Gesprächssituation z.T. mit manchem Gelächter, skizziert – von der Etikette des ‚deutschen‘ Haushaltes bis hin zu ‚Rudolf Hitler‘.

Das Gespräch vermittelt zudem einen Eindruck von der deutschen Sprache als Kolonial-, Herrschafts- und Dienstbotensprache: Die deutsche Sprache von Cecilie Kahimunu enthält auch Wörter in Afrikaans und in Otjiherero, ihrer Muttersprache: ‚Muhona‘ (Otjiherero): Herr (oder chief); ‚Baas‘ (Afrikaans): Herr, Boss; ‚Ovahona‘ (Otjiherero): die Herren (oder chiefs); ‚Ovikuria‘ (Otjiherero): die Speise; ‚Passiona‘ (Dienstbotensprache): verreisen, besuchen; ‚Omutango‘ (Preislied über Personen) – über Deutsche (oviduitji).

Mich fasziniert, wie hier die deutsche Sprache als koloniale Dienstboten- und Herrschaftssprache verwendet wird: Afrikanerinnen (und nicht immer Europäerinnen) erzählen über ihr erlebtes koloniales ‚Afrika‘.“

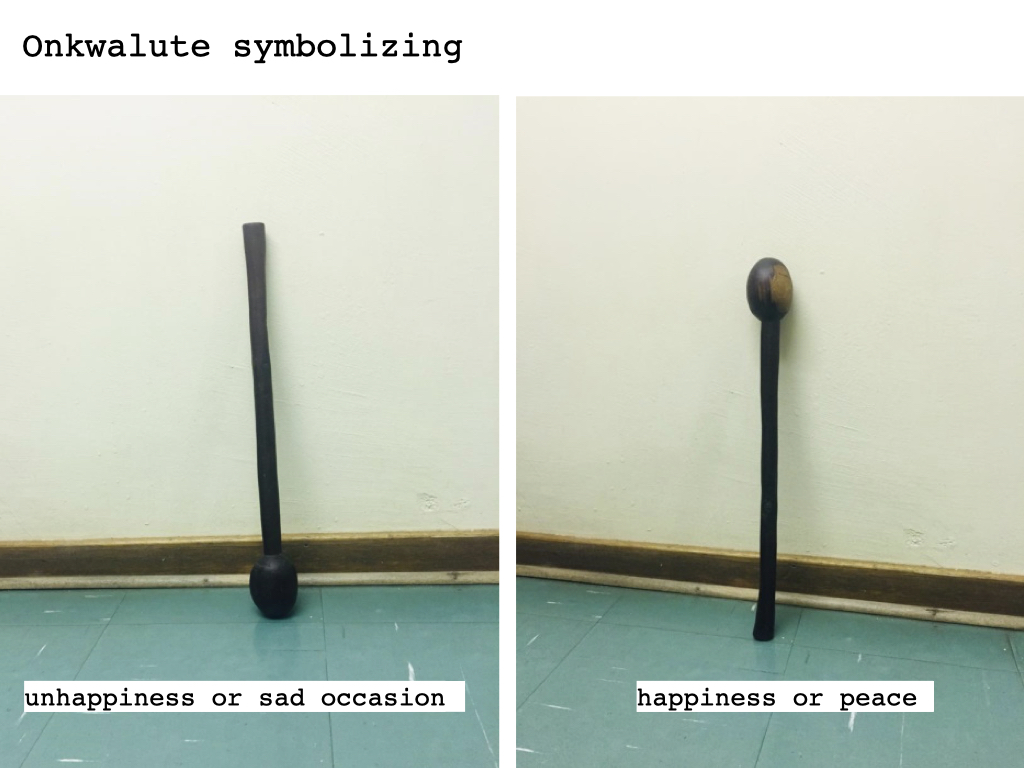

Petrus Angula Mbenzi / "Onkwalute" (knobkerrie)

A. Dr. Petrus Angula Mbenzi about himself:

I am the Oshiwambo lecturer at the University of Namibia. I have authored several school books and academic articles on oral traditions, onomastics, and linguistics of Oshiwambo. My research interests include onomastics, oral tradition, and sociolinguistics.

B. I chose this object, because …

… it plays a significant role in communication in Oshiwambo culture, but the language that this „onkwalute“ ‘speaks’ remains unrecorded in literature.

C. What narratives of Namibia do we encounter in it? Which sentence can be used to illustrate this?

„Onkwalute“ communicates a certain message to onlookers by the way it is carried. When an Omuwambo man holds the lower (staff) part of the „onkwalute“ while travelling, it shows that he is aggressive, but when he holds the middle part, it shows that he is peaceful. He may also throw it down when he meets someone to show that there is peace, especially if he was holding the lower part. A man may also hold the „onkwalute“ at the upper part near the knob to show that there is peace. If a man comes to a homestead, holding the lower part of his „onkwalute“ with the knob facing downwards, it shows that he wants to make trouble or it is a sign that he is offended by one of the family members. He may also hold his „onkwalute“ in this way if he has come to deliver bad news. This man will typically occupy the ‘troublemaker seat’ at the reception area („oshoto“). Both the seat and the way the „onkwalute“ is held conveys the message that there is no peace.

A man holds „onkwalute“ in the middle or towards the knob when dancing at the wedding party. A man may also express his joy at the wedding or show respect to a dignitary by hitting the ground with the „onkwalute“. The „onkwalute“ will also be leaned against a homestead’s palisade by a visitor with its knob facing downwards if he comes to a homestead where people are mourning. But if he comes in a homestead when there is a wedding ceremony, he would lean the „onkwalute“ against the palisade facing upwards. When one meets a man with an „onkwalute“ resting on his left shoulder held with the right hand, it means that this man is on his way to a homestead where people are mourning. When a man gets into an argument while being seated, he will express his annoyance by hitting the ground with his „onkwalute“ several times.

D. What do I find fascinating about this object?

„Onkwalute“ is not carried by women or young unmarried men. It is only carried by a married man when he makes a visit or when he travels. A man may use it in self-defence. Traditionally, a man who travels without an „onkwalute“ in his hand is construed as a coward or effeminate. „Onkwalute“ is carved from the „ongete“ tree (Kalahari Christmas tree).

E. What information do I think is important to understand this object?

To understand the „onkwalute“ one has to understand the way in which it is carried. Since he also has to carry bows and arrows when traveling, a man would usually hold the bow and arrow in his left hand and hang the „onkwalute“ from his waist belt on the right-hand side.

F. Which questions regarding this object have I not yet found an answer to?

It is not clear why women and young men are not allowed to carry the „onkwalute“. I have yet to find out why „onkwalute“ is mainly carved from a particular type of tree, the „ongete“ tree.

Foto: Basler Afrika Bibliographien

Foto: Basler Afrika Bibliographien

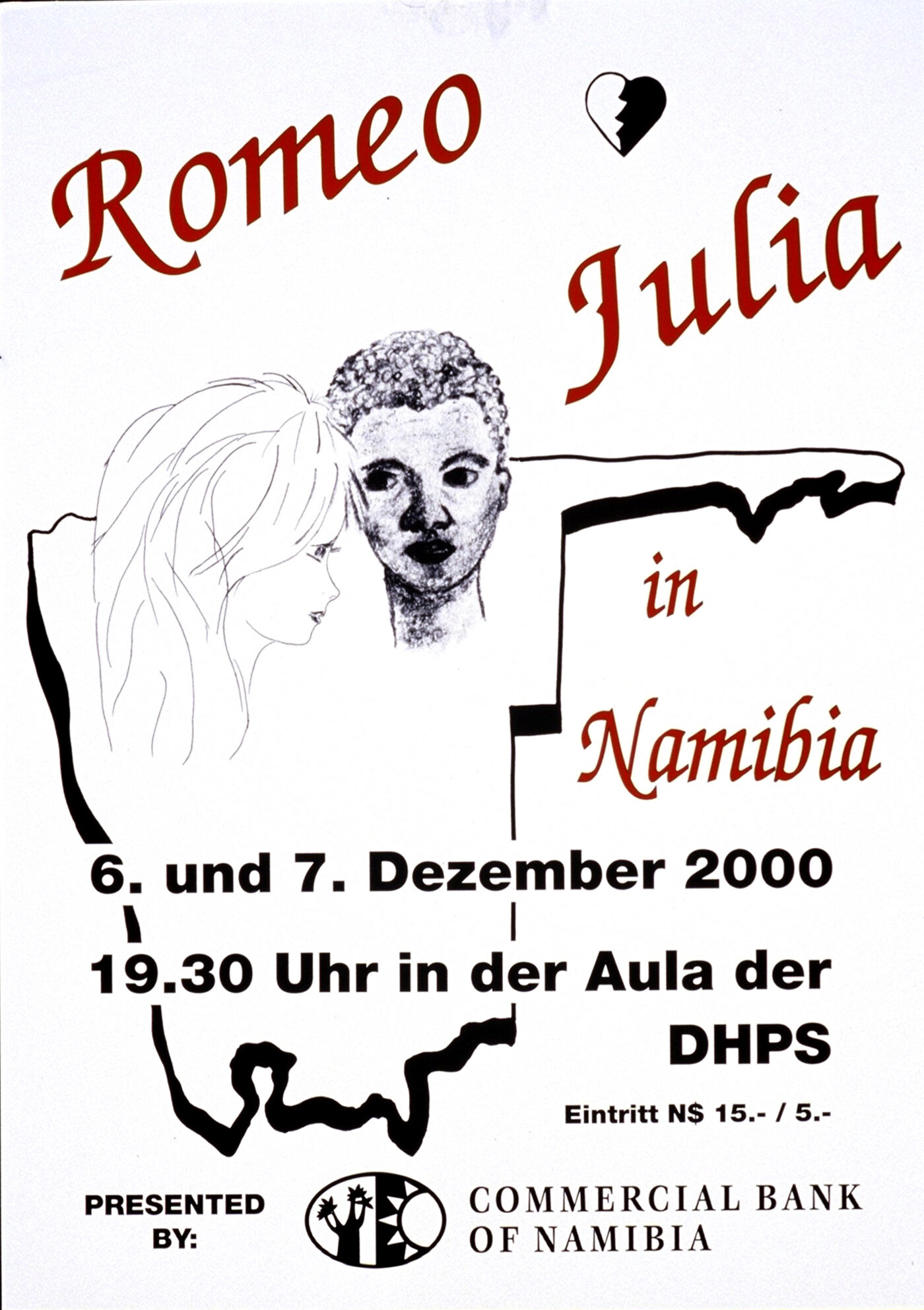

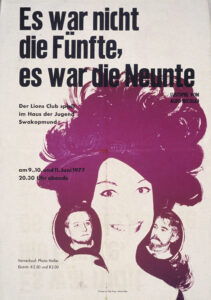

Dag Henrichsen / Theaterplakate aus Namibia

„Das Plakatarchiv der Basler Afrika Bibliographien verwahrt zahlreiche Theaterplakate aus Namibia, z.B.: ‚Romeo und Julia in Namibia‘ (BAB Sig. X 246) der Theatergruppe Deutsche Höhere Privatschule, Windhoek 2000 / ‚Es war nicht die Fünfte, es war die Neunte‘ (BAB Sig. X917), ein Theaterstück vom Lions Club Swakopmund im Haus der Jugend 1977 / ‚J. W. Goethe’s Urfaust“ (BAB Sig. 3844), ein Theaterstück von ‚Swakopmunder mach(t) Theater‘ im Woermann Haus 1999 / ‚Julien Geirises is Penelope‘ (BAB Sig. 3250), Theaterstück ‚The Namibian Odysseus‘ des National Theater of Namibia, Windhoek.

Die visuelle Sprache der Theaterplakate vermittelt unterschiedliche Themen – vom ‚deutschen Kulturimport nach Namibia‘ über Adaptionen (Romeo als Afrikaner, Penelope als Afrikanerin) bis hin zum Anti-Apartheidstheater (in Bern). Eine breite Palette von dezidiert literarisch-politischen Paradigmen und Paradigmenwechseln. Mich interessieren die Plakate als visuelle und öffentliche ‚marker‘ von Literatur und Kultur(politik) in (post-)kolonialen Alltagskontexten in Afrika und Europa.“

Sylvia Schlettwein / cast iron "potjie"

A. Sylvia Schlettwein about herself

I am a German-speaking Namibian, born on 16 November 1975 in Omaruru/Namibia. I grew up in South Africa and Namibia and studied at the Universities of Cape Town and Stuttgart. After completing my Master’s degree in Stuttgart, I returned to Namibia in 2003. I live, love and work in Namibia’s capital, Windhoek, where I write, translate, and edit short fiction, creative non-fiction, and poetry in English, German, and Afrikaans and teach German and French.

B. I chose this object, because…

I chose the cast iron potjie, because, even though it does not originate from Namibia and is also not unique to Namibia, it ‘contains’ stories and experiences of all Namibians. Regardless of whether we actually still cook our own food in a potjie or not, most of us have tasted food from a potjie and have a story to tell about that food: who made it, who ate it, where it came from, whether it was tasty, bland, or burnt.

C. What narratives of Namibia do we encounter in it? Which can be used to illustrate this?

The potjie contains stories of the privilege, hardship, joy, pride, and struggle to put food on the table – even if there is no table. If you open the lid, your nostrils might be hit by the aromatic fragrance of a meaty stew or a so-called ‘marathon chicken’ but also by the stench of burnt maize porridge. It might be filled with a steaming bread or it might be empty, either because the pot was licked clean or because there was nothing to put in it. Many potjies are covered in soot from standing in the flames and coals, while another potjie’s more shiny-grey than matte black appearance tells the story of an existence as a decorative and/or unused object.

The potjie gives you the narrative of cultural diversity in Namibia, of a sometimes dysfunctional, sometimes tight-knit patchwork nation with a love for socializing around the fire, of communal potluck and flavours that come together, but also the narrative of parallel lives and division.

While it certainly tells of our pre-colonial, colonial, and post-colonial history, it also holds the promise of contemporary, creative narratives: what a perfect accidental business start-up with an old family recipe, murder instrument, container of a magic potion that turns corrupt politicians into philanthropists, useless wedding present for a couple living in an apartment building, secret hiding place for cash or a couple of tiny aliens, to be continued …

D. What do I find fascinating about this object?

Personally, it fascinates me that something so unapologetically round and heavy is perched sturdily on three comparatively thin legs; I love that it comes with its own legs, it does not need a table to let everyone gather around it.

What I find most fascinating, however, is the multitude of smells and tastes, images, sounds, imaginary mini-movies, and emotions the potjie triggers in my head.

E. What information do I think is important to understand this object?

I discovered that the cast-iron cauldron probably originates from China, that it is also called a ‘Dutch Oven’ and replaced clay pots when European missionaries brought it to Africa. Nevertheless, I had to google this information, which shows how culturally integral and innate to Namibia I perceive this object to be. The Afrikaans word ‘potjie’ refers to the object as well as to a meat-based stew prepared in the pot over an open fire.

The tourism industry has, to a certain degree, commercialised the image of the potjie as well as that of the above-mentioned stew and thus reduced the narrative to one of Southern African hospitality and a rustic way of life – much like ‘traditional African dance performances’, having a potjie is offered to tourists as an ‘authentic’ African experience.

Nevertheless, the potjie is highly functional and used widely in Namibia for both celebratory and day-to-day cooking across all ethnicities. It is common in the sense that it is found in many Namibian households, and is thus not a special luxury item, but also in the sense of its being an object that all Namibians can relate to. However, one needs to understand that, while for some its significance lies in lazy weekends, holiday camping safaris, and the pleasure of good food enjoyed with family and friends, for others it is the epitome of daily squalor, a lack of electricity, and having to feed your family ‘mieliepap’ (maize porridge) every day.

F. Which questions regarding this object have I not yet found an answer to?

As I wrote this, I realised that countless questions and much more food for thought are still simmering in the potjie, too many to keep a lid on and too many to squeeze into 500 characters with spaces.

Fotos: Basler Afrika Bibliographien

Dag Henrichsen / "Namibia Today. Official Organ of the South West Africa People´s Organisation” (hier eine Ausgabe von 1984)

„‚Namibia Today‘ ist die weitverbreitete Zeitschrift der namibischen Befreiungsbewegung SWAPO, sowohl für die namibische Exilbevölkerung während des Befreiungskrieges (1966-1990) als auch für die internationalen Anti-Apartheids- und Sympathisantenbewegungen bestimmt. Sie wurde zeitweilig in Erfurt (DDR) gedruckt. Obgleich auf Englisch herausgegeben, wurde die Zeitschrift auch in Ost- und Westdeutschland verteilt. Die Redaktion(en) befanden sich in London und, in den 1980er Jahren, in Angola. Der zeitweilige Druck der Zeitschrift in der DDR war Ausdruck der SED Solidarität mit den afrikanischen Befreiungsbewegungen, in der DDR breit durch die ostdeutsche Bevölkerung abgestützt. Das Foto auf der Rückseite der ‚Namibia Today‘-Ausgabe spielt darauf an und zeigt zugleich ein weitverbreitetes Buch des DDR-Journalisten Alfred Babing.

Die in Berlin lebende Künstlerin Laura Horelli hat die Geschichte von ‚Namibia Today‘ und der Druckerei ‚Fortschritt‘ in Erfurt filmisch festgehalten und in einer in Berliner U-Bahnstationen installierten Kunstaktion thematisiert. Mich interessiert das internationale Netzwerk von Redaktionen, Journalisten und Druckern im Hinblick auf die Mobilisierung von antikolonialer Solidarität und die Bedeutung der DDR hierbei.“

Lade Audio…

Dag Henrichsen / Heinrich Vedder: "Südwestergeschichten" (Tonaufnahme 1953)

„Die z.T. verschriftlichten sogenannten ‚Südwester Geschichten‘, die von deutschsprachigen Namibiern erzählt wurden und werden, zeugen von einer vielschichtigen literarischen Oralität der Siedlergesellschaft (die sich zugleich als DIE lesende und schreibende Bevölkerungsgruppe Namibias verstand und immer noch versteht) und von ihren ästhetisierten kolonialnostalgischen, paternalistischen und zum Teil rassistischen Denk- und Weltbildern. Diese Geschichten zählen zum wesentlichen ‚Kulturgut‘ der deutschsprachigen Namibier.

Bei Heinrich Vedder, einem rheinischen Missionar, Ethnologen und Linguisten, dem 1925 die Ehrendoktorwürde der Universität Tübingen verliehen wurde, der in regem Briefwechsel mit Hans Grimm stand, von 1948/49 an Senator im südafrikanischen Aparheidsparlament und zentraler Verfechter der Apartheid in Namibia war, werden sie mit belehrendem Duktus vorgetragen.

Die Tonaufnahme mit Vedder stammt von dem Afrikanisten und Theologen Ernst Dammann (Berlin und Marburg), ebenfalls Verfechter der Apartheid und NSDAP-Mitglied.“

Du musst angemeldet sein, um einen Kommentar abzugeben.

Annika Böttcher: „Als Praktikantin am Deutschen Literaurarchiv (Frühjahr 2020) interessiere ich mich – beeinflusst von kindlich-naiven Afrikavorstellungen und einem entwicklungspolitischen Freiwilligendienst in Ruanda 2017/18 – ganz besonders für Literaturen von und zum afrikanischen Kontinent und für aktuelle Fragen der Entwicklungszusammenarbeit. Afrikanisch-Europäische Partnerschaften, die etwa zwischen Kulturinstitutionen bestehen, gründen häufig auf gemeinsamer kolonialer Vergangenheit. Umso wichtiger ist es, ungleiche Machtverhältnisse mithilfe

Annika Böttcher: „Als Praktikantin am Deutschen Literaurarchiv (Frühjahr 2020) interessiere ich mich – beeinflusst von kindlich-naiven Afrikavorstellungen und einem entwicklungspolitischen Freiwilligendienst in Ruanda 2017/18 – ganz besonders für Literaturen von und zum afrikanischen Kontinent und für aktuelle Fragen der Entwicklungszusammenarbeit. Afrikanisch-Europäische Partnerschaften, die etwa zwischen Kulturinstitutionen bestehen, gründen häufig auf gemeinsamer kolonialer Vergangenheit. Umso wichtiger ist es, ungleiche Machtverhältnisse mithilfe dieser Parterschaften aufzuheben und dauerhaft kritisch-reflektiert mit der Zusammenarbeit umzugehen. Der Anspruch, der damit einhergeht, nämlich an gleichwertige Partner gleiche Forderungen zu stellen, ist eine häufig idealisierende Marketing-Strategie, die mir besonders aus dem westlichen Kontext heraus bekannt ist und das allseits bekannte Märchen von der Augenhöhe vorgaukeln soll. Dass afrikanische Aktivistinnen und Aktivisten vor genau sechzig Jahren eine mehrsprachige Zeitung herausgaben, erscheint aus dieser Perspektive äußerst bemerkenswert und fortschrittlich.“