Namibia is one of the focal points of the „Narrating Africa“ project. Researchers and writers based in Windhoek today present Namibian literature and objects.

Julia Augart / Ed. by Sylvia Schlettwein and Erika von Wietersheim: "Hauptsache Windhoek. Fast drei Dutzend Geschichten und Gedichte" (2013)

A. Julia Augart about herself:

I hold a PhD from the University of Freiburg and have taught German language and literature at various universities on the African continent. Currently, I am a Professor of German at the University of Namibia. My research focuses on German literature and crime fiction set in Africa and on German-language Namibian literature. I enjoy reading African fiction.

B. I chose this text, because …

It is difficult to choose something, but as a Professor for German in Namibia I like „Hauptsache Windhoek“, which not only comprises Namibian literary texts in German, but is also a quite recent collection of short stories, poems, and photographs of various authors and backgrounds describing Windhoek, the capital of Namibia. Various aspects of the past and the present, everyday life, beliefs, customs but also prejudices and tensions of this multicultural and multilingual city are portrayed and give an insight into the city, its people and their notions about the city – it is also a stimulating idea to portray a city through literary texts.

C. What narratives of Namibia do we encounter in it? Which sentence can be used to illustrate this?

The collection presents various views of different groups, although unfortunately it is not clear which texts were originally written in German and which were translated. „Hauptsache Windhoek“ shows that the past is traceable not only in colonial houses and street names, but also in the memories of people. This shows that there are different cultures living together often not knowing enough about each other. It shows the vast gap between rich and poor. It shows that Windhoek is beautiful and at the same time not. It shows sights in Windhoek that are not in the guidebooks. It shows that there is still a German speaking minority in Namibia writing in German. It shows funny encounters, streetwiseness… It shows …. so many things.

„Meme Kauna ist ausgesprochen zufrieden, als sie in den städtischen Bus nach Katutura steigt. Das Riesenpaket unter ihrem Arm ist schwer und unbequem zu tragen, aber ihr Herz ist leicht. Ein Gemälde in einem goldenen Rahmen! Wie es das kleine Wohnzimmer ihres einfachen Hauses in einen vornehmen Raum verwandeln wird! Der Neid der Nachbarn! Wie großzügig von Madam Carla, ihr dieses farbenfrohe Bild im goldenen Rahmen zu schenken. Da sieht man’s doch wieder, die jungen weißen Leute sind gar nicht mehr so schlimm wie ihre Eltern. Die Zeiten haben sich wirklich geändert. Sogar die weißen ‚Madams‘ von Windhoek teilen heutzutage ihre Kultur mit ihren schwarzen Angestellten. ‚One Namibia, one Nation! The struggle is over‘, oder?“

D. What do I find fascinating about this text?

The different stories and poems paint a very diverse picture. In its everyday aesthetic, its everyday language and its short everyday stories, it reveals a very realistic picture and presentation that one recognises when living in this city. It also shows that Namibia has a small body of literature written in German which contributes to the various literatures in the country and is part of the Namibian literary landscape.

E. What information do I think is important to understand this text?

I do not think that one really needs to have additional information to understand these texts. Rather, these texts help the reader to get a better understanding of Windhoek or Namibia and its people. Maybe the texts trigger an interest to learn more about the past (colonial times and Apartheid) as well as the present of Namibia and to look at Windhoek from a different perspective. However, I do believe that the more one knows about Namibia, the role Germany played in its past, Namibia’s multicultural society, the inequality and problems in the country, the more one can also understand the narrations and the ironic or critical portrayals or plot twists.

F. Which questions regarding this text have I not yet found an answer to?

‘One Namibia, one Nation!’ – when will this be achieved?

Why do we not have more collections like this that also include other voices and other languages for an even more diverse portrayal and juxtaposition of different voices and narratives as this collection focuses more on authors writing in German?

Jekura Uaurika Kavari / Kuaima Riruako: "Ya ri aiyerike"

A. Jekura Uaurika Kavari about himself:

I am an Associate Professor who lectures on Otjiherero language and Literature at the University of Namibia. The literature course includes elements of cultural and oral history as contexts in which this literature is set. I have taught Otjiherero at the University of Namibia for thirty-four years now.

B. I chose this text, because …

… it fascinates me how the late Ovaherero Paramount Chief Kuaima Riruako mirrors the agony of the Ovaherero community and the distorted history of Namibia from the perspective of ethnic groups of the Republic of Namibia. Today, those who have lost their ancestral land and suffered the most are ignored and treated like second- or even tenth-class citizens of Namibia.

C. What narratives of Namibia do we encounter in it? Which sentence can be used to illustrate this?

In the wars that were fought in Namibia during colonial times, it was the Ovaherero community alone that opposed their oppressors, and it was this community that was colonised, while other Namibian communities simply watched its attempts to resist the invaders or intruders or aggressors or colonisers, or whatever you may call them. This text emphasises the leading role of the Ovaherero community, but also the fact that it suffered most compared to other Namibian communities. The sentence ‘ya ri aiyerike’ (literally ‘it was it alone’) illustrates the suffering, agony, torture, and misery this community alone went through during these wars. That is why today the Ovaherero and the Nama communities expect an apology, which includes admission of guilt and expression of regret, and reparations that will heal the wounds and suffering of the affected communities from the German government.

D. What do I find fascinating about this text?

It poetically captures the history of Namibia in a nutshell. It narrates how the Ovaherero community was involved in the wars against colonisation and oppression from the outset and how they suffered in these wars.

E. What information do I think is important to understand this text?

This text emphasizes the major involvement of the Ovaherero community in the wars against colonialism and oppression, even though today in independent Namibia the general view is that its involvements had been of little or even no significance. In the past, when the Ovaherero were the dominant power in central Namibia, they refused to give any land to the Germans. That is why Maharero gave a bucket of soil to the Germans, symbolising his refusal. When the Germans rose to power following the genocide wars through sheer force, they reserved the ‘crone’ land for German settlers. This refers to the area northwest of Windhoek, north of Gobabis, west of Okahandja and southwest of Otjiwarongo. When South Africa took over power from the Germans after the First World War, Boers (Afrikaners) devised the Odendaal plan in order to demarcate farm land for white South Africans (especially the Boers), who subsequently settled there, while black Namibians were driven out of those areas. When the Ovambo came to power (after the Independence of Namibia), they resettled their fellow Ovambo at the expense of all other Namibians.

F. Which questions regarding this text have I not yet found an answer to?

When are we going to re-organise ourselves into the country we envisaged before independence? The Namibia we hoped for when we cried ‘one Namibia, one nation’. A country in which all ethnic communities become one nation and create a new society. A country free of corruption, fraud, inequality, greed, favouritism, nepotism, racial discrimination, self-enrichment, and disunity – all of which are the order of the day in the independent Namibia today.

Source of text: Mbaeva, NK. 2018. „Omukambo mOtjiherero. Learners’ book“, page 176. Windhoek: Namibia Publishing House.

Nelson Mlambo / Vickson Hangula: “The Show Isn’t Over Until” (1998)

A. Nelson Mlambo about himself:

I am a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Language and Literature Studies at the University of Namibia. My area of specialisation is Literary Studies and Theory and I currently teach literature modules which include ‘An Overview of African Literature’, ‘Namibian Literature in English Since Independence’, and ‘Postcolonial and Commonwealth Literature’.

B. I chose this text, because…

My text of choice is Vickson Hangula’s „The Show Isn’t Over Until“ which is set in post-independence Namibia. I am fascinated by this play because it is a bold and unflinching portrayal of the ‚unsaid‘ and ‚unasayables‘ that glaringly haunt present-day Namibian society. The issues raised in the play are presented in a certain manner that makes one feel like reading the play in hiding as the playwright confronts the social ills with such boldness that is scary.

C. What narratives of Namibia do we encounter in it? Which sentence can be used to illustrate it?

In the play, one is confronted with the stomach-churning narratives of corruption that reminds one of the Fishrot scandal; the horrors of embezzlement that is practised by those in positions of authority, especially with their sense of entitlement stemming from the proverbial excuse ‚we died for this country‘, as well as the cancer of racial and tribal intolerance, stereotyping, and superiority complex.

D. What do I find fascinating about this text?

„The Show Isn’t Over Until“ juxtaposes power and powerlessness, and the bitter irony of post independent disillusionment. What I find fascinating about the play is its style, particularly its use of the dramatic device of a play within a play; the use of humour and also the use of realism that evokes a feeling of verisimilitude. I also find the playwright’s daring attitude towards confronting certain realities intriguing.

E. What information do I think is important to understand this text?

In reading the play, it is important to keep one’s own prejudices and preconceived ideas at bay so that one can fully participate in the dynamics of the play. This is because the manner in which the play narrates Namibian realities demonstrates the cyclical nature of history and that the more things change, the more they remain the same.

F. Which questions regarding this text have I not yet found an answer to?

The question that remains unanswered after closely reading this play is this: is it possible to dream of a Namibia with better tribal and racial integration? With the ending of the play as it is, how can one imagine and / or re-imagine the future, especially if this is asked in relation to the fields of decoloniality and the Afrotriumphalist theorisations.

Rémy Ngamije / Ange Mucyo: "Subterwhere" (2019)

A. Rémy Ngamije about himself:

I am a Rwandan-born Namibian writer and photographer. My debut novel „The Eternal Audience Of One“ is forthcoming in August from Scout Press (S&S). I write for brainwavez.org, a writing collective based in South Africa. I am the editor-in-chief of „Doek!“, Namibia’s first literary magazine. My short stories have appeared in „AFREADA“, „The Johannesburg Review of Books“, „American Chordata“, „Azure“, „Sultan’s Seal“, „Columbia Journal“, and „New Contrast“. I have been longlisted for the 2020 and 2021 Afritondo Short Story Prizes and shortlisted for the 2020 AKO Caine Prize for African Writing and the Commonwealth Short Story Prize. More of my writing can be read on my website.

B. I chose this text because…

I chose „Subterwhere“ by Ange Mucyo because it is the first piece of psychological horror from Namibia that was published to international acclaim. Mucyo is a Namibian writer, network and systems administrator, software developer, and Cisco-certified network associate by profession. He also dabbles in 3D art and sound production. Mucyo is interested in computers and video games and the opportunity they provide to bring these various art forms together in an interactive context. Subterwhere was published in „Doek! Literary Magazine“ in August 2019: https://doeklitmag.com/subterwhere/. At the time, „Doek! Literary Magazine“ had just launched its first issue and most of its content as solicited from a small group of Windhoek-based writers. „Subterwhere“ was the only piece from the group which did not follow so-called African storytelling conventions. Its choice of subject matter was novel and exciting, its pacing was measured, and its slow-burn tension was captivating.

C. What narratives of Namibia do we encounter in it?

Avoiding the cliché milieus of the Namibian wilderness and its landscapes, this short story explores interior settings. However, colonial confrontation makes a brief appearance in the narrative.

Which sentence can be used to illustrate this?

‘Sometimes I think about all the lamenting over what was lost when the white man came looking for us to do the work he didn’t want to do. The lives, the stories, the potential, the world we lost. And now, I see what’s missing in those lamentations. The warnings.’

D. What do I find fascinating about this text?

I enjoy the departure from what I call the tourist gaze. There is a specific kind of writing about Namibia that has been propagated by white tourists visiting the country: the writing strips locals of all imagination and individuality and relegates them to the ‘smiling, friendly natives’ one encounters in tired and biased colonial literature. This story is bold and asserts itself into the Namibian literary landscape without paying any respect to the local storytelling habits. It challenges the local, national, and international reader with its plot and language.

E. What information do I think is important to understand this text?

Very little – this story does not explicitly state that it takes place in Namibia. However, anyone who is intimately familiar with Windhoek will be able to pick out subtle nuances which pin down the location of the story. Thus, the story works on two levels: it rewards the international reader with an approachable story, and it is especially rich for the local who is able to discern the meta-descriptions and narratives in the story.

F. Which questions regarding this text have I not yet found an answer to?

I am yet to fully understand whether this story is a commentary on the encounter with the other. What is it that the narrator sees? Or feels? In my imagination it is not something extraterrestrial. Rather, it is a subtle shift in the narrator’s perception of reality. I have yet to decide whether the source of the disturbance is external or internal.

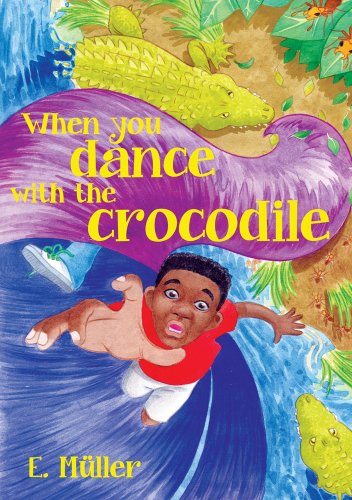

Juliet Silvia Pasi / Erna Müller: "When You Dance with the Crocodile" (2012)

A. Juliet Pasi about herself:

I am a senior lecturer in the Department of Communication at the Namibia University of Science and Technology (NUST). I teach language, communication, and literature courses. My research interests are environmentalism in literature, issues of gender in literature as well as children’s literature. I am the editor-in-chief of the NAWA „Journal of Language and Communication“ at NUST. I am currently working on a book manuscript provisionally titled: „Ecofeminism, the Environment and Cultural Resistance in African Women’s Fiction“.

B. I chose this text, because …

… it is a children’s technology-cum-computer novel. Müller, a Namibian writer of children’s books, chronicles the lives of children in a contemporary technological Namibian literary setting. While the novel exhibits artistic craftsmanship and creativity, it also illustrates technological and computational practices which underpin the Fourth Industrial Revolution. As such, this text is a computational novel which introduces principles of computational thinking to Namibian children and illustrates computer science concepts and their application in a literary, fairy-tale-like domain.

In the novel, Helena, her brother Sam, Matsimela, and Ruth learn critical thinking, debating, and creative problem-solving skills as they follow online instructions and thus enter a wormhole that teleports them into a dangerous computer game and takes them to the Caprivi Strip in ancient Africa. This kind of critical orientation allows them to explore complex human-to-human as well as human-to-robot relations. In a tech-driven era, it is crucial that such relations be explored within a creative literary context, in children’s literature etc.

The novel is educative. It conscientizes and warns both children and adults that not all computer games have educational content. Some computer games influence children to act violently. In July 2019, a 10 year old boy in Katutura, Windhoek, committed suicide after playing a game called ‘the momo challenge’. As part of the challenge, the players are urged to harm themselves or even commit suicide after receiving an image of a woman with bulging eyes on their phone.

C. What narratives of Namibia do we encounter in it? Which sentence can be used to illustrate this?

The novel presents the following narratives of Namibia:

1. Life in Windhoek. Members of a neighbourhood watch meet to discuss strategies to combat crime.

2. The treatment of women and girls as fragile and vulnerable. The way Dr Amadhila treats his daughter Helena.

3. The proverb ‘when you dance with the crocodile’ plays a significant role in the socialisation process. It admonishes one to avoid bad behaviour.

4. The lives of people in ancient Africa, under the rule of the Paramount Chief Lewanika of Sesheke village and the Mukwai, the queen.

D. What do I find fascinating about this text?

What I find fascinating about this novel is that it underscores the interaction of technology with humans, and humans with technology. For instance, the creation of a dangerous computer game by Mark reveals the impact of programmed technology using coding and robotics upon children’s lives. Through the 7H device (a super modern cell phone with a GPS), the Namibian children in the text receive online instructions from Mark, and they are finally teleported back to present-day Windhoek. In all these instances, the novel illustrates not only the value of literary studies, but also that humanistic concerns are inseparable from technological advancement. The Fourth Industrial Revolution has, quite understandably, focused on STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) and whilst this focus is both laudable and necessary, „When You Dance with the Crocodile“ can be used to argue that there is a need to move towards STEAM (science, technology, engineering, the (liberal) arts, and mathematics), which caters for the affective/arts domain. As such, the humanities should not be dismissed as an anachronism; instead, according to STEAM proponents, technology can only benefit from being infused with humanistic ideas and impulses to fulfil its objective of human betterment. Precisely such inclusivity may help to bridge the gap between the humanities and sciences.

E. What information do I think is important to understand this text?

To understand the novel, one needs to understand:

1. The meaning of the Namibian proverb ‘when you dance with the crocodile’. This helps one to understand the significance of the title. In the novel, Matsimela’s task is to stop the chief’s son Dimdimbara from drinking. On one occasion, when Matsimela realises Dimdimbara is getting drunk, he tips over his drink and warns him that if he keeps drinking, he will be a bad chief one day.

2. The Namibian cultures and belief systems before modernisation.

3. The computational practices in the novel. These include:

Programming

In Dr Amadhila’s words:

‘It’s the human element, … A computer does what you programme it to do. It’s a machine. But a person is different. You can’t programme a human.’ (p. 63)

In the novel, Mark is a professional programmer. To create the dangerous game, and build in a language tool into the game, he uses codes; a language that the computer understands and executes. The language tool enables the players of the game to understand and speak the languages of the people they come across. Mark also creates an automatic pilot and a brake system into the game. To understand the novel, one requires familiarity with the programming concept but not knowledge of programming.

Codes

Coding is essentially written instructions that a robot or computer programme can read and then execute. Mark uses codes to create language instructions. Through the 7H device the children receive online instructions from Mark, and they are teleported from ancient Africa back to present-day Windhoek.

Algorithms

An algorithm is a procedure or formula for solving a problem, based on conducting a sequence of specified actions.

Helena and Sam follow procedures to get to an Africa from centuries past (1889) to save Ruth and Matsimela. Instructions are created, for example:

‚i. The red letters ‘A Dangerous Game’ flicker on the computer screen.

ii. Click the mouse.

iii. Experience real life adventure. Danger lurks everywhere. Continue if you dare.

iv. Click on continent.

v. Click on wherever you want to land.

vi. Click on a picture.

vii. Please read the following instructions carefully before starting your journey and click on ‘Play the game’ when you are ready.

viii. Choose the level of difficulty: difficult, very difficult, extremely difficult, or diabolically difficult.‘ (pp.8-10)

The wormhole then comes and sucks in everybody near the computer.

Artificial intelligence

Artificial intelligence (AI) is the simulation of human intelligence processes, operations and capabilities by machines, especially computer systems. In the novel, the programme created by Mark locates Helena in the Caprivi Strip in Namibia, identifies the wormhole used by Helena, and links Mark to Helena’s 7H device.

F. Which questions regarding this text have I not yet found an answer to?

1. Why was the Queen in ancient Africa cruel and punished people by throwing them in the river where they would be eaten by crocodiles?

2. What is the symbolism of the colour red (the Queen hates this colour)?

3. Is it possible to stop the creation of such dangerous computer games?

Helen Vale / Neshani Andreas: "The Purple Violet of Oshaantu" (2001)

A. Helen Vale about herself:

From 1991 to 2008 I taught in the English Department at the University of Namibia (UNAM). Prior to that I taught at the University of Swaziland for four years. My special interest is Namibian literature in English and I am currently working with Prof. Sarala Krishnamurthy (Namibia University of Science and Technology) and Dr Nelson Mlambo (UNAM) on the second and third volumes of our book series on Namibian writing (across all languages and genres) since independence. It has just been accepted for publication by a well-known European publisher. The first volume, an anthology of 22 chapters, is entitled „Writing Namibia, Literature in Transition“ and was published by UNAM Press in 2018.

B. I chose this text, because …

… I am intimately connected to it because I knew Neshani as my student in the mid-1990s at UNAM, then as a member of the publications sub-committee on the Archives of Anti-Colonial Resistance and the Liberation Struggle (AACRLS)* project and later as an occasional guest speaker for my first-year students. Amazingly, she had given me the manuscript around 1998 to read! Little did I know then that it was to become the first Namibian novel to be published in the prestigious African Writers Series, thanks to the support of Jane Katjavivi, at that time owner of New Namibia Books which greatly supported new authors.

C. What narratives of Namibia do we encounter in it? Which sentence can be used to illustrate this?

– friendship and support between women (Aili, the narrator and Kauna, in particular)

– different kinds of men/masculinity: supportive and loving vs. abusive and patriarchal (Michael vs. Shange)

– feminism: psychological strength of women, challenges women face in a patriarchal society (particularly after their husband’s death)

– vivid evocation of life in a village in the north of a Namibia and traditional beliefs

– conservative, patriarchal attitudes of the church, particularly towards widows

– inheritance practices in northern Namibia where the deceased husband’s family often claims the house and cattle, leaving the widow and her children destitute

„Kauna to Aili after the sudden death of her husband Shange.

‘Well, I’m sorry you all feel uncomfortable about my behaviour, but I cannot pretend,’ she shook her head. ‘I cannot lie to myself and to everybody else in this village. They all know how I was treated in my marriage. Why should I cry? For what? For my broken ribs? For my baby, the one he killed inside me whilst beating me? For cheating on me so publicly? For what?’“(p. 49)

D. What do I find fascinating about this text?

Neshani was a modest and diffident person. I never suspected she would go on to become a creative writer, but she was brilliant at capturing rural life in northern Namibia, particularly friendship between women, power of patriarchy, and harmful inheritance practices.

E. What information do I think is important to understand this text?

The fact that Neshani’s original title was different and it was changed to „Purple Violet“ (as seen on the front left of the cover) at the suggestion of the editors. This then tied to the repeated motif in the novel with Kauna, the main protagonist, as ‘the purple violet’, a beautiful and strong woman.

F. Which questions regarding this text have I not yet found an answer to?

Sadly, Neshani died relatively young, only a few years ago in 2011, but she apparently left an almost completed manuscript of a second novel. Was this novel also set in rural northern Namibia? Was it in any way a follow-up to the first novel? Will it ever see the light of day?

*AARCLS – is the Archives of Anti-Colonial Resistance and the Liberation Struggle.

It was a ten year joint project between Namibia and Germany, whose aims included finding and publishing manuscripts (autobiographies) related to the Namibian liberation struggle (1966–2000) in order to diversify and democratise the archive.

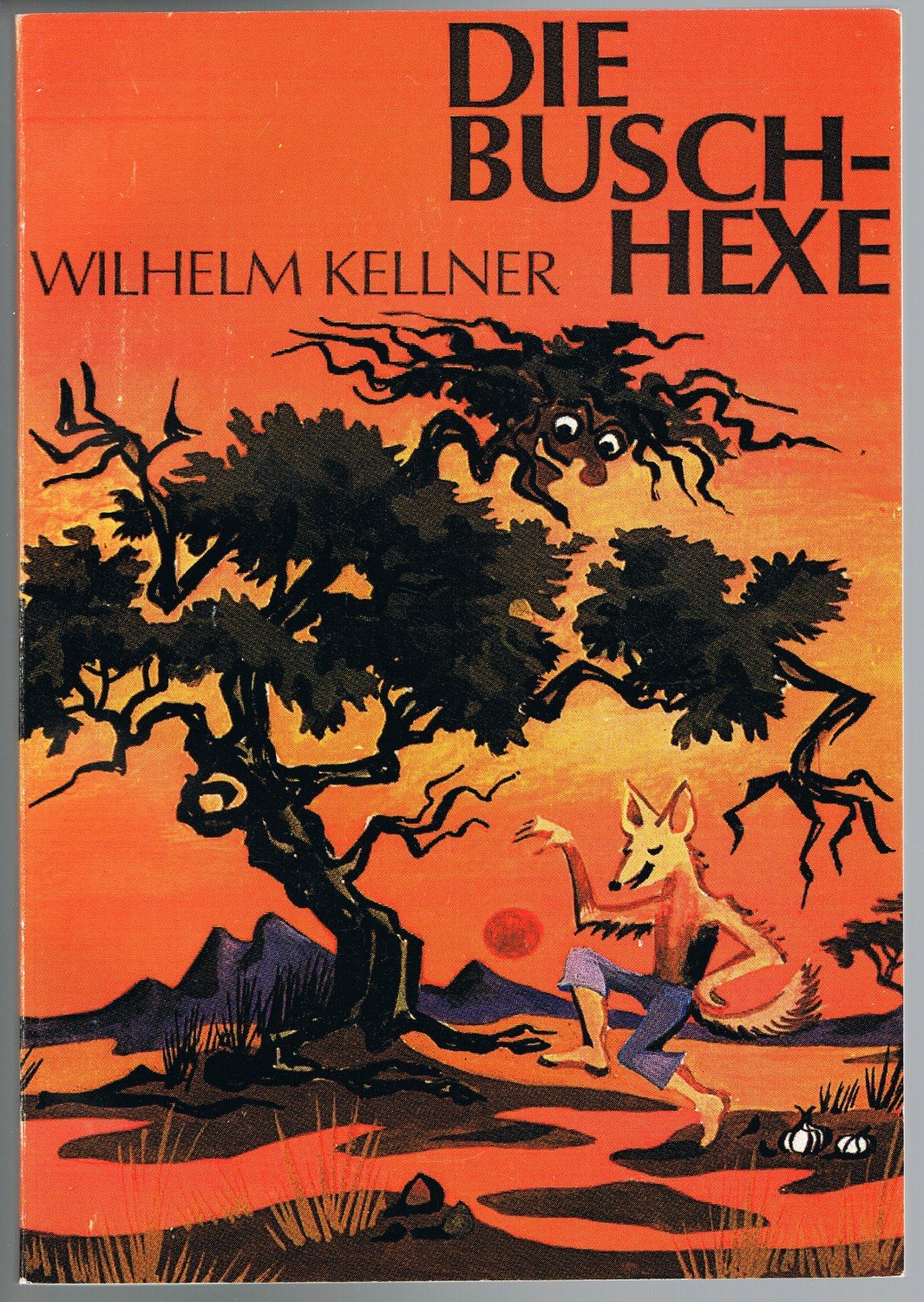

Marianne Zappen-Thomson / Wilhelm Kellner: "Die Buschhexe" (2015)

A. Marianne Zappen-Thomson about herself:

I was born in Grootfontein and grew up in Otavi, Namibia. I studied German and Philosophy at Stellenbosch University, completed my MA in German and obtained my D.Litt. I worked as a teacher of German as a Foreign Language before becoming a lecturer and later full professor at the University of Namibia. I have published widely in the field of German in Namibia, intercultural communication, translation studies and German as a Foreign Language.

B. I chose this text because …

I chose Wilhelm Kellner’s „Die Buschhexe“ (1976), an anthology of twelve Namibian fairy tales for children covering various topics like the water snake, the singing mountain, the bush witch, and the chief with the rain magic. The fairy tales all fit into the country’s natural and social setting although it does become obvious to the adult reader that they date back to the 1930s.

C. What narratives of Namibia do we encounter in it?

As a child, my parents and I would sit on the veranda in the evenings; I snuggled deeply into the protecting arms of my mom, and they would read German fairy tales to me. I marvelled at the snow, the gingerbread house, the castles and much more, but somehow, I could not really relate to it. Then, one evening my mom started reading from a different book, and all of a sudden the new fairy tales made sense. I knew the sound of the jackal, and I could envisage the thorn tree standing next to the dry riverbed.

D. What do I find fascinating about this text?

The water snake is most probably the best-known image used in a number of fairy tales belonging to various cultural groups of Namibia. In this tale, the water snake drinks all of the water in the country, causing terrible draughts. Nobody is able to kill it. Instead, the snake kills the young girls it is offered as sacrifice and eventually threatens to kill all of the people in the country. ‘Wo sie hinkam, trank sie die Quellen und die Wasserstellen leer, so daß weit und breit eine große Trockenheit herrschte. Das Wild im Busch und das Vieh im Kral verendeten.’ This clearly shows the great despair resulting from draughts in Namibia.

Another fairy tale relates to the loss that farmers have to endure when wild animals kill their sheep. Wanting to explain this conflict to children, Kellner uses the figure of the bush witch, who transforms a naughty little boy into a jackal. Needing food to survive, the boy/jackal decides to kill a lamb. Just moments before he gets shot by a local farmer, who of course wants to protect his lamb, the jackal is transformed back into a little boy. ‘Der Farmer fuhr aus dem Schlafe auf und dachte: Die Schakale werden mir die Schafe holen, erhob sich, griff zum Gewehr und sah draußen einen Schakal sitzen. In diesem Augenblick hatte Friedrich endlich die kleine Zwiebel zwischen den Wurzeln einer mächtigen Akazie gefunden. Freudig verschlang er sie, da krachte es…’

The importance of the ancestors as well as of rain forms the narrative of another fairy tale, which is clearly set in the north of Namibia along one of the rivers. Leleimo, the greedy chief of the community, does nothing to lighten the suffering of his people, who are trying their best to cope with the lack of rain that has caused the mahangu (a type of grain) to die in the fields. Instead, Leleimo demands that his people hand over to him the food that they gathered or hunted. If they do not obey, he orders his subordinates to drown them in the river, claiming that the food is rightfully his. The ancestors, appearing in the form of crocodiles, hear this. They decide to save Kweti from drowning and chase the selfish chief Leleimo to the island in the river. Leleimo’s kind-hearted nephew, Ndunda, becomes the new chief. „Das Krokodil hieß Karuku und war um eine Schwanzlänge größer als seine Gefährten. ‚Wie?‘ knurrte es, ‚wir sollen schlechter sein als die Menschen, die uns Hinterlist und Mordgier vorwerfen und uns deshalb verfolgen und töten? Habt ihr den tückischen Leleimo gehört? Wir wollen einmal den Spieß umdrehen und zeigen, daß wir besser sind als der Alte.‘“

E. What information do I think is important to understand this text?

This anthology written in German for the children in this country with its vivid and fascinating style shows that the environment – so different from the nature depicted in traditional German fairy tales – offers a setting for fairy tales which is just as rich and one that Namibian children can relate to. The harsh nature, in which these fairy tales take place, allows them to clearly visualise what is happening. Furthermore, it opens up the world of the different cultural groups that live in Namibia, but were historically kept apart.

F. Which questions regarding this text have I not yet found an answer to?

I think it is important to know that this anthology was written in 1934 during a time when Namibia, then known as South West Africa, was under the mandatory governance of South Africa with its politics of keeping different groups of people segregated. The families in the stories therefore either belong to the more privileged white group or they are black people who either live in rural areas or are employed by white people. However, Kellner succeeds in depicting the relationships among these people with respect and dignity. He uses images that pertain to the country without committing cultural appropriation but allowing them to remain in their traditional setting. It is thus not a white girl who encounters the water-snake, but Kalanda, the daughter of an old magician. Apart from this, „Die Buschhexe“ is a true fairy tale-anthology which is timeless and is understood as well as accepted by children.

Coletta M. Kandemiri / Ed. by Naitsikile Iizyenda and Jill Kinahan: "My Heart in Your Hands" (2020)

A. Coletta M. Kandemiri about herself:

I am recently graduated with a PhD from the University of Namibia. I completed my Master’s Degree in English Studies at the same university. I am interested in learning more about the creatures that we define as social beings and I do this by indulging in diverse literature on diverse people.

B. I chose this text, because …

I chose „My Heart in Your Hands“ because it contains a variety of poems that all relate to Namibia. The poems express the poets’ personal experiences on a variety of issues. The poets have very diverse backgrounds and the poems have different themes that include inequality and injustice amongst other themes that relate to Namibia’s people and topography. I am intrigued by the way the poems are grouped under captions such as: Where the Ocean and Desert Kiss; Mothers of Namibia; Fighting the Storm Within, that give an overall theme associated with each grouping. Poetry allows for graceful expression and the anthology provides profound insights into Namibia, the land, and its inhabitants.

C. What narratives of Namibia do we encounter in it? Which sentence can be used to illustrate this?

A number of poems celebrate the exquisiteness of the desert. A desert is usually perceived as ‘uninhabitable’ and therefore lifeless, but the poets find charm in that spaciousness. The poems remind the readers of the positivity that exists in the desert, celebrating Namibia’s beauty that is embedded within the desert. The following lines are taken from the poem ‘Only Namibia’ (p. 5); they express the country’s beauty as it is observed by the poet:

1I come from a country where the ocean and the desert kiss

2Beautiful piece of savannah and sky

The beauty of Namibia lies in its distinct natural features: the vast desert lands meet the ocean, a vast body of water. The poet is proud of the land and asserts the existence of life in a desert.

The poem ‘Katutura’ (p. 18) refers to a part of the city of Windhoek that was constructed during the colonial era and is perceived as a very dangerous place:

1They will tell you that Katutura is too dangerous

However, to the poet Katutura is a dynamic haven with a positive atmosphere. The young and the old all play critical roles that breathe life into Katutura as becomes evident in the following lines:

8It is a place where children’s joy echoes from one street to another.

9Where neighbours gossip with microphones yet still keep open secrets silent.

10Katutura breeds the bravest of hearts

11and strongest of wills

12and most loveable people.

13Katutura greets you with a friendly smile each day

14never waves goodbye

15and is always there.

It is through this poem that Katutura is given a profile instead of being described or stereotyped as a place of repulsive deeds. In the two poems ‘Only Namibia’ and ‘Katutura’ the desert is thus viewed as a place full of live, where humans prosper and call ‘home’.

D. What do I find fascinating about this text?

What I find fascinating about this anthology is that many poems emphasize the beauty of the landscape, sundry cultures, as well as the diverse backgrounds of the Namibian people, and a whole lot more. The anthology also brings together the voices of different people speaking about Namibia and it allows them to share their personal views and perceptions.

E. What information do I think is important to understand this text?

One needs to understand the harshness of any desert environment in order to be able to appreciate the positive affirmations expressed in some of the poems. One also needs to have a general knowledge of Namibia’s historical and political background, which influences the writing of certain poems. Lastly, one needs generally to appreciate poetry as a form of writing that provides profound insights for both the poem and the poet.

F. Which questions regarding this text have I not yet found an answer to?

There are some poems in the anthology whose authors I wish I could contact in person and find out what exactly their poems refer to. Poetry requires engagement beyond the surface of the text; in most cases it carries a deeper and hidden meaning. So, I am curious to know what the poets are referring to or what it is that their poems signify.

Sarah Situde / Lucia Engombe: "Kind Nr. 95" (2004)

A. Sarah Martha Situde about herself:

I am a twenty-nine-year-old high school teacher, born and raised in Namibia. When I was two, my mother learned to speak German, which first sparked my own interest into the language. However, my German-language journey did not fully start until I was in eighth grade. After I left high school, I went on to study Education in university, majoring in German and Afrikaans. After completing my BeD/Honours degree, I decided to further my studies by enrolling in a master’s programme in German Studies.

B. I chose this text, because …

In high school I kept hearing the term ‘DDR-Kids’ [GDR children]. As time passed, I learned that they had one common quality: speaking German. Later, I came across the autobiography of Lucia Engombe and I found out that she too was a ‘DDR-Kid’, so I read her autobiography. I greatly admire Lucia Engombe, and especially the career she chose. Both of us, as Namibians who learned German, developed a passion for it and decided to pursue a career in it. This is why I chose this text.

C. What narratives of Namibia do we encounter in it? Which sentence can be used to illustrate this?

In her autobiography, Engombe describes how everything seemed new and different, when she returned to Namibia from Germany, and also how promises that were made (to her and the other ‘DDR-Kids’) were not kept. „‚Ihr seid die Elite des neuen Namibia‘, hatte uns der Präsident gesagt, als wir in Bellin noch kleine Kinder gewesen waren. Hatte er das vergessen? Ich wusste es noch. Ich wollte keine goldenen Schüsseln, um daraus zu essen. Ich wollte mich nur nicht belogen fühlen.“ (p. 274)

D. What do I find fascinating about this text?

It is fascinating how the (German) host culture influenced the (Namibian) mother culture of Engombe and the other GDR children in this autobiography. This autobiography proves that the early childhood stages have a major impact on a child’s future. Additionally, the linguistic creativity of the children is amazing. They created their own language ‘Oshi-German’, and this can be understood as them re-creating their own identity in a foreign country.

E. What information do I think is important to understand this text?

One should be familiar with the history of the GDR children and of the liberation struggle between Namibia and South Africa at the time. The fact that Germany was divided and Namibia was not yet independent is important to know, too. The journey of the GDR children was politically motivated. Engombe was very young when she came to Germany and it was not always easy for her and the others. The GDR children were exposed to German culture, which influenced their future. They were sent to Germany to become the future elite of Namibia, but upon abruptly returning to Namibia in 1990, they had to come to terms with their new life in Namibia.

F. Which questions regarding this text have I not yet found an answer to?

Can Lucia Engombe be considered a transnational and transcultural person? Did she want to go back to Germany? Why did the promise of the government, in particular, the SWAPO, not materialise? What happened to the majority of the GDR children?

Schreibe einen Kommentar

Du musst angemeldet sein, um einen Kommentar abzugeben.